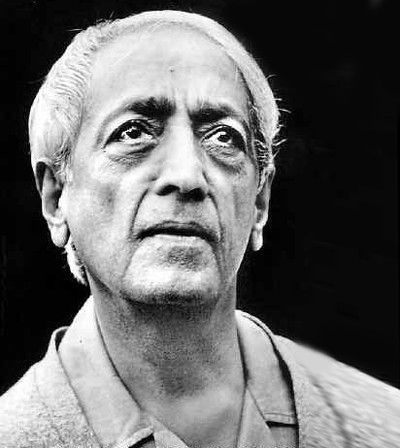

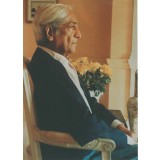

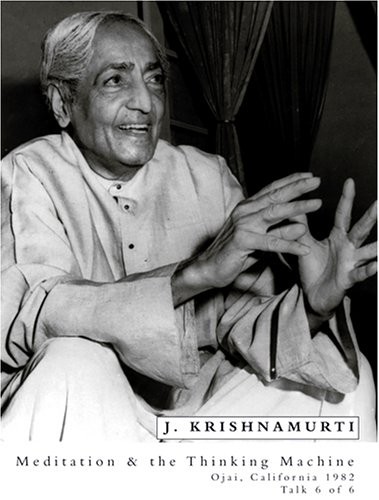

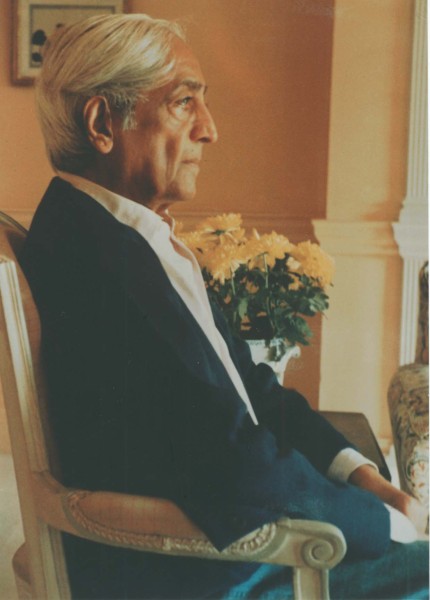

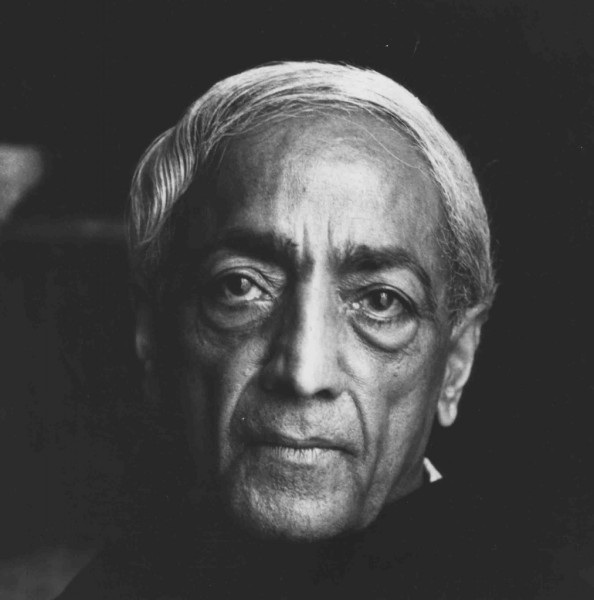

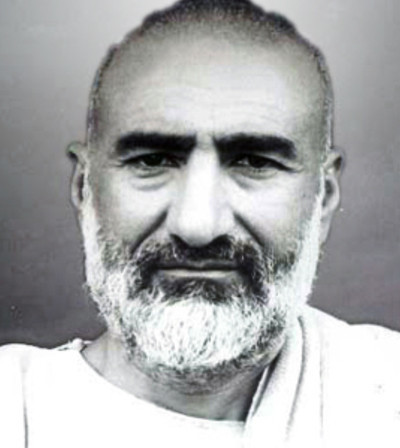

Born

May 12th, 1895

Passed Away

February 17th, 1986

Popularly Known as

J. Krishnamurti

Occupation

public speaker, author, philosopher

Religion

Hindu

Native

Madanapalle

Country

India

પિતા જ ધર્મ છે, પિતા જ સ્વર્ગ છે, પિતા જ પરમ તપ છે, પિતૃભક્તિ સર્વે ભક્તિમાં શ્રેષ્ઠ છે. પિતૃભક્તિ સર્વે દેવતાઓને પણ પ્રિય છે. શાસ્ત્ર માં કહેવાયેલા આ વાક્યો નો અર્થ અમારા જીવનનો મર્મ છે. સ્વર્ગની પ્રાપ્તિ ધર્મથી થાય છે, તપથી થાય છે. પરંતુ અમારા માટે અમારી પિતૃભક્તિ જ સર્વે ભક્તિમાં શ્રેષ્ઠ છે.

Shradhanjali By

Shradhanjali .com

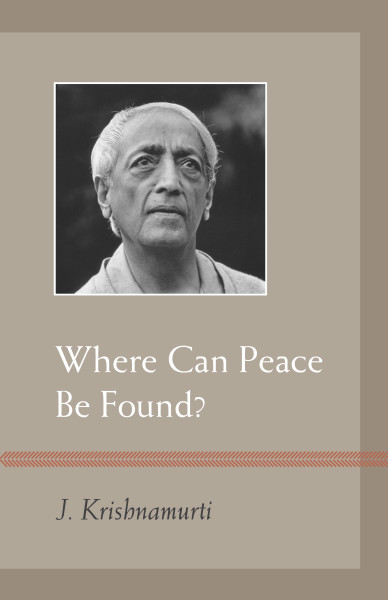

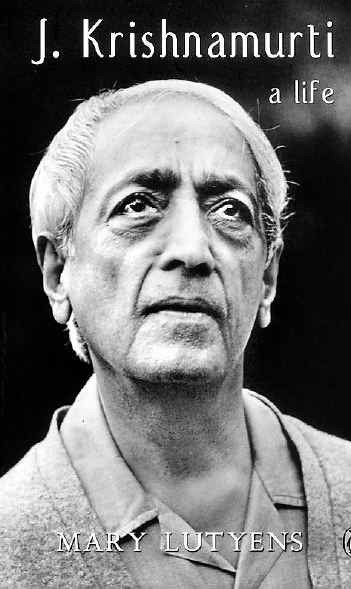

Biography of Krishnamurti Narainiah Jiddu

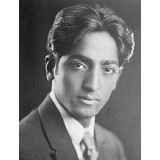

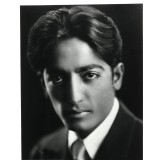

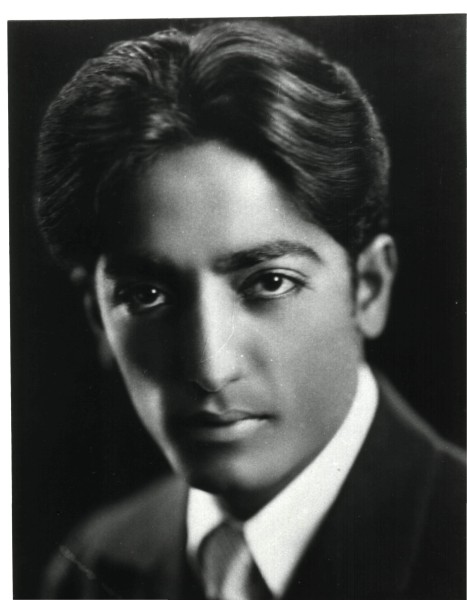

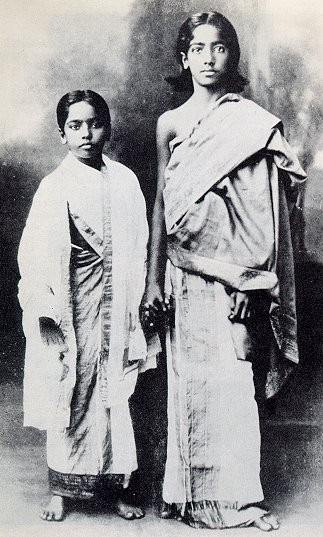

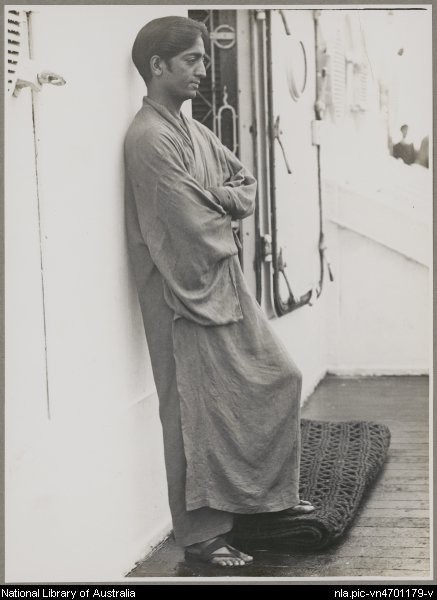

Jiddu Krishnamurti was born on 11 May 1895 in Madanapalle, a small town in south India. He and his brother were adopted in their youth by Dr Annie Besant, then president of the Theosophical Society. Dr Besant and others proclaimed that Krishnamurti was to be a world teacher whose coming the Theosophists had predicted. To prepare the world for this coming, a world-wide organization called the Order of the Star in the East was formed and the young Krishnamurti was made its head.

In 1929, however, Krishnamurti renounced the role that he was expected to play, dissolved the Order with its huge following, and returned all the money and property that had been donated for this work.

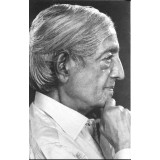

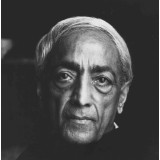

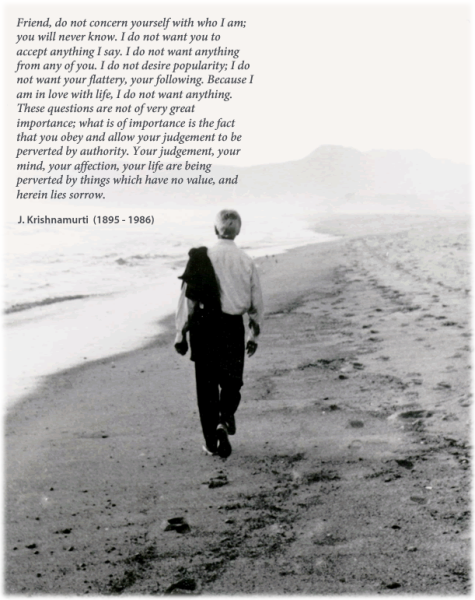

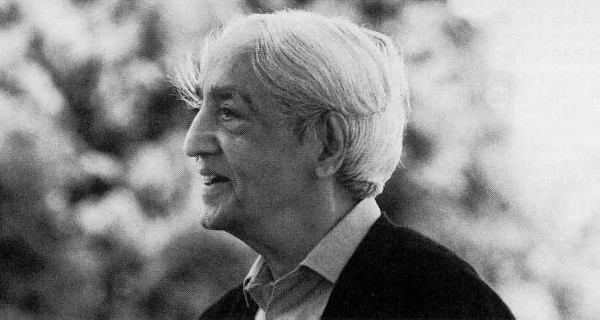

From then, for nearly sixty years until his death on 17 February 1986, he travelled throughout the world talking to large audiences and to individuals about the need for a radical change in mankind.

Krishnamurti is regarded globally as one of the greatest thinkers and religious teachers of all time. He did not expound any philosophy or religion, but rather talked of the things that concern all of us in our everyday lives, of the problems of living in modern society with its violence and corruption, of the individual's search for security and happiness, and the need for mankind to free itself from inner burdens of fear, anger, hurt, and sorrow. He explained with great precision the subtle workings of the human mind, and pointed to the need for bringing to our daily life a deeply meditative and spiritual quality.

Krishnamurti belonged to no religious organization, sect or country, nor did he subscribe to any school of political or ideological thought. On the contrary, he maintained that these are the very factors that divide human beings and bring about conflict and war. He reminded his listeners again and again that we are all human beings first and not Hindus, Muslims or Christians, that we are like the rest of humanity and are not different from one another. He asked that we tread lightly on this earth without destroying ourselves or the environment. He communicated to his listeners a deep sense of respect for nature. His teachings transcend man-made belief systems, nationalistic sentiment and sectarianism. At the same time, they give new meaning and direction to mankind's search for truth. His teaching, besides being relevant to the modern age, is timeless and universal.

Krishnamurti spoke not as a guru but as a friend, and his talks and discussions are based not on tradition-based knowledge but on his own insights into the human mind and his vision of the sacred, so he always communicates a sense of freshness and directness although the essence of his message remained unchanged over the years. When he addressed large audiences, people felt that Krishnamurti was talking to each of them personally, addressing his or her particular problem. In his private interviews, he was a compassionate teacher, listening attentively to the man or woman who came to him in sorrow, and encouraging them to heal themselves through their own understanding. Religious scholars found that his words threw new light on traditional concepts. Krishnamurti took on the challenge of modern scientists and psychologists and went with them step by step, discussed their theories and sometimes enabled them to discern the limitations of those theories. Krishnamurti left a large body of literature in the form of public talks, writings, discussions with teachers and students, with scientists and religious figures, conversations with individuals, television and radio interviews, and letters. Many of these have been published as books, and audio and video recordings.

A Brief Introduction to Krishnamurti's teachings

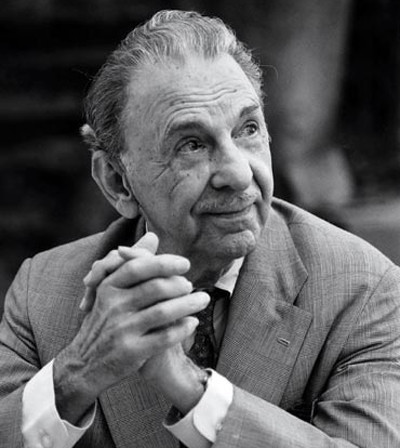

by Professor David Bohm (formerly of Birkbeck College, University of London)

My first acquaintance with Krishnamurti’s work was in 1959 when I read his book The First and Last Freedom. What particularly aroused my interest was his deep insight into the question of the observer and the observed. This question had long been close to the centre of my own work as a theoretical physicist who was primarily interested in the meaning of the quantum theory. In this theory, for the firs time in the development of physics, the notion that these two cannot be separated has been put forth as necessary for the understanding of the fundamental laws of matter in general.

Because of this as well as because the book contained many other deep insights, I felt that it was urgent for me to talk with Krishnamurti directly and personally as soon as possible. And when I first met him on one of his visits to London, I was struck by the great ease of communication with him, which was made possible by the intense energy with which he listened and by the freedom from self-protective reservations and barriers with which he responded to what I had to say. As a person who works in science, I felt completely at home with this sort of response, because it was in essence of the same quality as that which I had made in contacts with those other scientist with whom there had been a very close meeting of minds. And here, I think especially of Einstein who showed a similar intensity and absence of barriers in a number of discussions that took place between him and me. After this I began to meet Krishnamurti regularly and to discuss with him whenever he came to London.

. . . Krishnamurti’s work is permeated by what may be called the essence of the scientific approach, when this is considered in its very highest and purest form. Thus, he begins from a fact like the nature of our thought processes. This fact is established through close attention, involving careful listening to the process of consciousness, and observing it assiduously. In this, one is constantly learning, and out of this learning comes insight into the overall or general nature of the process of thought. This insight is then tested. First, one sees whether it holds together in a rational order. And then one sees whether it leads to order and coherence in what flows out of it in life as a whole.

Krishnamurti constantly emphasizes that he is in no sense an authority. He has made certain discoveries, and he is simply doing his best to make these discoveries accessible to all those who are able to listen. His work does not contain a body of doctrine, nor does he offer techniques or methods for obtaining a silent mind. He is not aiming to set up any new system of religious belief. Rather, it is up to each human being to see if he can discover for himself that to which Krishnamurti is calling attention, and to go on from there to make new discoveries on his own.

Family Tree of Krishnamurti Narainiah Jiddu

Sanjeevamma Narainiah Jiddu

Profile Home

Profile Home Biography

Biography Family

Tree

Family

Tree Photo

Album

Photo

Album Video

Video

Post Condolences